“I wondered if the motto for our era should be: I tried to live but I got distracted.” — Johann Hari

What are you thinking about right now? Before continuing, pause for 30 seconds and try to focus on each breath you take, counting how many times your mind wanders.

This sort of mind wandering is both natural and unavoidable. In fact, a “short” attention span is not necessarily a bad thing. Boredom has evolutionary advantages and can be thought of as an internal signal for when our time is not providing an adequate return on investment. In other words, we’re not designed to spend hours upon hours deeply focused on a single task, but we’re also not designed to spend nearly no time at all in a focused state.

In 2004, when computers had already begun to take over the attention of consumers, the average “attention span” of an individual as measured by how long individuals spent on a single page before switching to another task was two and a half minutes. By 2012, the figure had dropped to 75 seconds (notably 5 years after the release of the first iPhone). In past years, the average attention span has dropped to about 47 seconds.

It’s hard for many of us to fathom what life was like before personal distraction devices in the form of phones and computers became commonplace. I actually tried to recreate this scenario while on vacation recently through what I called a “phone fast” where I didn’t check my phone all day. It was both liberating and anxiety-inducing. A blend between oh well, I’ll get to it later and oh no, what if the world is falling apart.

So you might be thinking, sure this is a problem, but what does it have to do with my health? From my perspective, the war on our attention is impacting our health in the following ways:

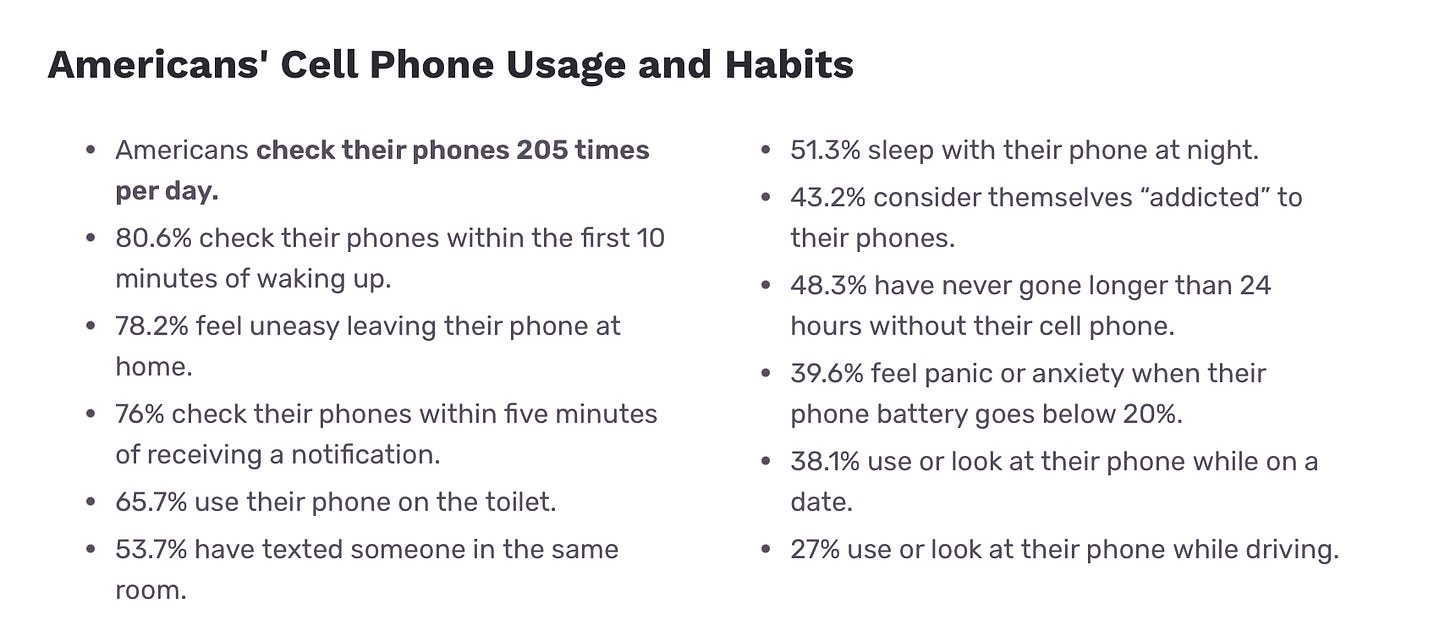

Distraction is preventing meaningful human connection: A recent report showed that Americans pick up their phones ~205 times per day — roughly once every 5 minutes. Our time spent enveloped in technology and detached from those around us is keeping us from building and maintaining relationships. You can have the perfect fitness and eating regimen, but if you’re lacking deep and meaningful human connections, the type that are cultivated through present and deliberate interactions, it’ll be all for naught.

Constant task switching is making us less effective in our pursuits: In Cal Newport’s 2016 best seller, Deep Work, he argues that one of the key detractors from focused work is “busyness as a proxy for productivity.” How often have you found yourself focused on a task only to be drawn away by a message? Unfortunately, quick responses to these instant messages are rewarded if not revered in today’s work environment. They break us out of bouts of focus and create “attention residue” that continues to impact us, even if we return to our previous task. Think about it like riding the bike at the gym. If we need to ride a bike until we reach 300 calories, but every minute or so we need to get off and do 20 squats, not only are we suffering from the transition time but our ability to ride the bike is also impacted. By the end, those squats will add up and impact our performance on the primary exercise itself. This all sums to less effective use of our time, meaning less time spent pursuing what truly matters to us.

Our ability and opportunity to learn is being substantially diminished: One argument I often hear to justify social media use is that it facilitates “learning.” I don’t think this is worth arguing since it is technically true. However, every activity has its tradeoffs. Time spent scrolling through social media takes us away from other meaningful learning opportunities and chances to make meaningful human connections. Distraction, whether because we’re using a device, or even thinking about using a device, is preventing us from learning more about ourselves, others and the world around us.

When the internet first exploded, there was optimism that we’d adapt—build filters to block out the noise and focus only on what mattered. We’d get better at finding the needles (what we needed to know) in the haystack (available information). But that future never came. Instead, we’ve created a world where every app, platform, and ping is optimized to hijack our attention. We didn’t get better filters—we got a haystack sized pile of needles.

This may seem quite doom and gloom given there’s no scenario where the prevalence of devices and frequency of their usage decreases in the coming years. However, I’m optimistic that if we change how we use technology, we can be happier, healthier, and better at our jobs — a win, win, win.

Stepwise strategies

Life

Stop using your phone as a social crutch. In the grocery line with your partner? Checks email. At dinner and the conversation dies down? Scrolls social media. In the passenger seat of a car? Checks status of a flight that’s in 26 days because the airline notified you. It’s more likely than not that whatever you’re checking can wait, whereas you’ll never recoup that time.

Break the click loop. I often see, and am guilty of, what I’d call the “click loop” on a cell phone. Click Instagram, check a few stories…ok nothing new. Now to Snapchat… respond to a message. Ok, now Twitter, take a few scrolls, laugh, refresh the page, take another few scrolls. Ok, now back to instagram. And the loop continues. I use the app Clearspace, a tool that requires a deliberate pause before opening other selected apps, to break this loop.

Create a playlist for workouts. Distraction is not only impacting our work and relationships; it disrupts practically every part of our lives. Part of the issue is that checking our devices is easier than whatever else we’re doing. Don’t let the act of changing a song during your workout become a 5 minute exercise of distracted scrolling.

Work

Block time and create a ritual for deep work. Cal Newport outlines one of the most critical paradoxes of our time: just as deep work is the most valuable it has ever been, it is harder than ever to focus deeply. Block time in your day to work intentionally without distraction. Let the quality of your work speak for itself.

Avoid “just checking.” As mentioned earlier, we check our phones an average of 205 times a day, and the urge to “just check” is largely to blame for this, especially in demanding jobs where we’re “on the clock” for most of the day. It may be counter-cultural, but set boundaries for when you’ll check your phone and respond to messages. Even when you “just check,” you’re left with lingering thoughts, yet nothing you can do about them.

Allow time for consumption, ideation and creation. We spend much of our day on tasks that are particularly susceptible to distraction: managing inboxes, scheduling meetings, status checks, etc. These activities, while necessary, are prohibitive of the things that help provide meaning to our work and lives such as learning and creating. Block time to consume new information, come up with new ideas, and create what you think the world needs.

Resources

Next Newsletter

We’ll discuss rucking

Excellent! Thanks for the helpful information

Good information and practical and useful suggestions.